“Ofelía has infected me with this postmodern

sickness”, says Siggi in Byggingin (The Structure). He doesn’t

know any manners any more, and all over the place there are robots in

glass cages who try to control his behaviour; they order him to flush

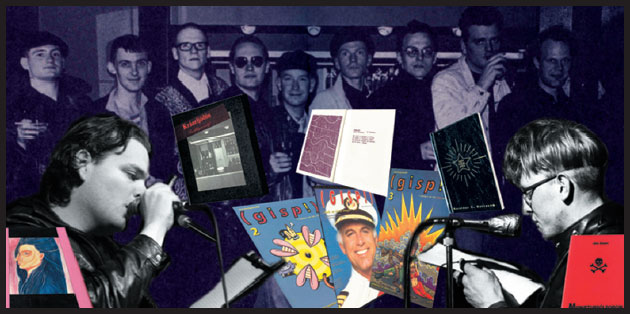

the toilet, for instance. The Structure is a novel by Jóhamar that

Bad Taste published in 1988 - a year later they followed it up with Jón

Gnarr’s Midnætursólborg (Midnight Sun City). Those

were good days. One alternative work after another, and when I look back,

that for me is the most memorable period of Bad Taste’s output.

I acquired a whole new faith in Icelandic literature; as a university

student I was of course totally preoccupied with everthing that wasn’t

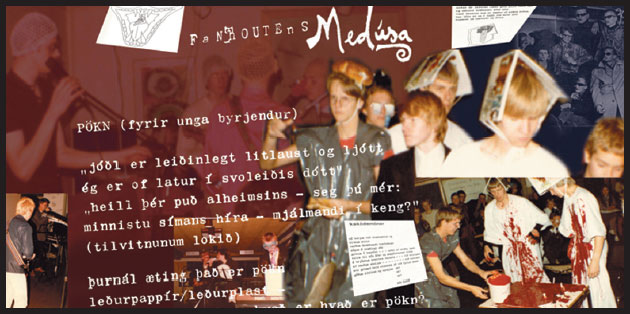

middle of the road. Actually at the time I was obsessed with the Medúsa

group, and stated straight out that Bad Taste was some sort of heir of

Medúsa. And then wrote a learned piece in Ársrit Torfhildar

(the literature students’ magazine) where I compared the poems of

the Medúsa poets to the Sugarcubes’ texts and claimed to

find some similarities.Can’t forget Kráarljó›in

(The Tavern Poems) either; that’s where the connection between Medúsa

and Bad Taste became beautifully clear, as lots of the poets were former

Medúsa members. I pull all this out to emphasize how much Bad Taste

is a multimedia enterprise.

1991. I’m writing a BA thesis. Which of course was supposed to be

the BA thesis to end all BA thesis (and was, too). The main focus of the

thesis is the writings of Sjón; then I brought in the two Bad Taste

novels and Kristín Ómarsdóttir’s short story

collection Í ferdalagi hjá flér (On a Trip with You).

The theme is eroticism, and I thought I was really avant-garde and fearless

- I read Story of the Eye to pieces, The Story of O, the Marquis and more

along that line, became exceedingly educated in pornographic literature,

and felt in my essence as spokesperson for these marginal works. (And

got what I paid for; to this day I still get email and phone calls requesting

me to express my views on pornography - me, who completely fell off the

bandwagon after The Correct Sadist, and hasn’t read anything cruder

than a Britney Spears lyric for a long time.)

2003. Twelve years later I sit down at the computer to write about these

Bad Taste novels, which have aged

well, both in my memory and in re-reading. Both stories take place in

the future, and show the influence of Burroughs, cyberpunk and other dystopic

science fiction; in both instances an interesting attempt is made at imagining

Reykjavík as a rough-edged international city, in a wreck after

unnamed horrors, pollution, war. The Structure tells the story of Siggi

and Ófelia. Siggi is unlucky enough to have recently discovered

“that he was a mortal man, one of a few. Earthlings had basically

stopped dying because of unexpected progess in the chemical industry.”